White Professors Who Teach Race and Diversity Not Uncommon at Illinois

Some UIUC students may be surprised to find when they walk into their African-American music class that their professor is a white man.

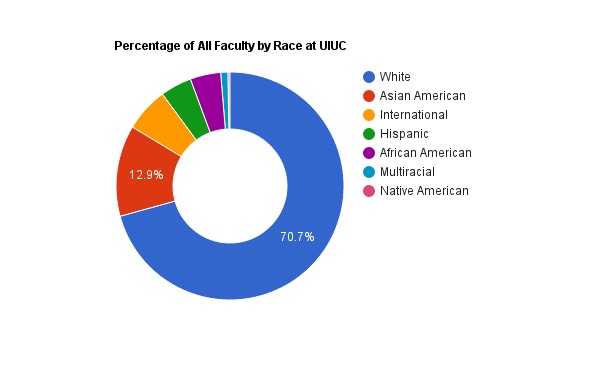

“I know that I have some sort of double takes from students when they walk in and see me the first time,” Professor John Paul Meyers said. Meyers is a visiting assistant professor in the African American studies department who identifies as white. His educational background is in ethnomusicology, and he teaches not only a course called African-American music, but also a course called Black Music and Social Justice. However, Meyers is not exactly an anomaly. Far from the only white professor to teach topics of race and diversity at the university, Meyers is, in fact, one of seven white professors to be listed as core faculty in the African-American studies department. Race and diversity-related courses became a popular topic of discussion on campus in the spring semester of 2016. In May, the UI senate passed the Chancellor’s Committee on Race and Ethnicity’s proposal to change the general education requirement from taking either a U.S. minority culture course or a non-western culture course to making both a requirement for students starting in Fall 2018. Despite the upcoming increase of students taking courses on U.S. minority and non-western cultures, there are no mandatory diversity trainings for professors who teach these types of courses, according to Associate Chancellor for Diversity Dr. Assata Zerai. Diversity-related trainings and committees vary by each academic unit, Zerai said via email. According to Ross Wantland, Director of Diversity and Social Justice in the Office of Inclusion and Intercultural Relations, because there is soon to be an increase in students taking these types of classes, reflecting on whether these classes are taught in effective ways is important. Wantland himself is a white professor who teaches on topics of race and diversity. He is a lecturer for PSYCH 496 - Facilitating Intergroup Dialogue. He said that, as a white person, he has to be aware of his white privilege and taking accountability for that. “There’s ways through both my privilege identities but also through my professional status that I can kind of obscure times that I might say something that is racist, that has a racist impact on people,” Wantland said. “So I also have to model for myself and for others what that means to kind of make mistakes and own them rather than use the tools I have at my disposal to make them disappear.” Wantland also said that he finds that people often listen to his voice over people of colors’. “People think it is amazing that a white person is teaching this,” he said. “I see more there is this really obnoxious privileging of my voice as the supposedly unbiased person in the room around race issues because “Well I’m white so I must possibly not have anything to gain around dismantling racism.”” Meyers said that listening to contributions student of color voices in class is key. “I think that that is particularly sort of important for white professors teaching about these issues, and understanding that we may have an academic understanding of some of these issues, and we may know the literature quite well, but there’s a difference in lived experience,” Meyers said. Other professors admit that they have not thought as much about their white privilege. Nils Jacobsen, professor in the Department of History, is teaching a Latin American History class this semester. He said that he does not have a very acute awareness when it comes to considering his white privilege. “To be honest I’m not sure that I do very much of that. I mean I encourage students and particular students from disadvantaged groups to come talk with me,” he said. “I don’t have a systematic sort of mental grid - they’re saying this or they’re doing this because they’re coming from a historically disadvantaged group. I have a problem with white privilege - this is not constantly in my mind I will grant you that.” According to a “Racial Microaggressions Report” that came out in 2015, over 51% of students of color on campus who participated in the survey said they experienced stereotyping in the classroom. Over 27% of students said that they were made to feel inferior or that their contributions were minimized because of their race. Stacy Harwood was one of the principal investigators of the Racial Microaggressions Report. She said that when students of color confront professors about microaggressions on campus, they often felt unheard or dismissed. “More often than not the instructor resists hearing that information - they listen, say “thank you very much” and don’t make any changes. And I think it was really hard on the students.” John Smith, a senior in engineering that identifies as Turkish and Muslim, recalls listening to a student in his Class and Race in America class make a broad generalization about Turkish people who join ISIS. He said that his white teacher did not challenge the student’s statement. “I would assume most teachers would have the wherewithal to say ‘That’s a pretty bad insinuation’,” he said. “It just kinda went completely unchecked which struck me as a very interesting stance.” One student, Jane Doe, a freshman who identifies as a multiracial Latina, said that all her teachers, save for one lecturer, are white this semester. She said that students of color are always going to have to brace for a professor saying something upsetting. Although she finds it important to confront professors in situations where microaggressions may have occurred, she said it is not always possible to address the situations in class. “I think that the only time I felt that my instructor has not outrightly acknowledged [white privilege] is when my discussion leader totally tried to suggest that reverse racism was real and that she could experience racism as a white woman,” she said. “And I was surrounded by white people and I was like ‘Today’s not the day, you got to pick and choose your battles.’” Harwood said that these types of interactions can have a negative effect on students’ learning experiences. “If it was just one time maybe it could be treated differently, but because students are having these interactions in multiple places on campus, it begins to feel like a very heavy weight on you,” Harwood said. “[Common thoughts are] ”I don’t feel like I belong” or “I’m not learning things to help me and my ideas” or “I don’t see myself as confident” or “I don’t see myself in this profession.” Students also report that having a professor of color teach them about race would be beneficial to them. Jane Doe said that she was surprised that inoa white professor was teaching one of her classes on race. “It wasn’t like I thought that he wasn’t qualified. It was just that I was a little bit disappointed because I feel like there are definitely Black professors that could be teaching this subject,” she said. “I would have preferred to have a Black teacher teaching me about a Black subject. It just would’ve made me more comfortable.” Adrian Burgos, Professor in History and Latino/a Studies, cited an incident that occurred last year when explaining the importance of having professors of color. In April 2016, unidentified students chalked Pro-Trump, anti-immigrant rhetoric in front of the Latino/Latina Studies building, an act that Burgos said many felt was a targeted attack. At this time, he was teaching a course called Latinos and Cities. “My students were hurting. They needed a space, an intellectual space, not just a space of counseling. A space where they could articulate the very real lived and psychological dimensions through what they have studied - application of their education,” Burgos said. He also said that he thinks that white faculty could have facilitated the same discussion, but the effects are different. “For my Latino students on that day in that space I think they felt comforted that they had a Latino professor to talk about it, to address it.” As of Fall 2015, 70% of total campus faculty is white. Asian-American faculty make up 12.8% and Native American faculty make up .3%. African-American and Hispanic faculty make up 4.3% and 4.4%, respectively. Professor Burgos said that one of the reasons that there may be a lack of professors from historically disadvantaged groups is because of the campus climate surrounding race and diversity. He spoke about the challenges facing retention of faculty members from historically disadvantaged groups. “Illinois desires faculty of color, most universities on a certain level do. There’s this early period of welcoming and romance and stuff, “We really want you at Illinois!’” Burgos said. However, Burgos questions whether development of faculty of color is as strong 10 or even 15 years out. He notes that creating pathways for scholars to become assistant professors and leaders at the university is just as important as being welcoming in the beginning. “Does the university develop its own scholars of color? As not just kind of stakeholders locally within race and ethnic studies units, but as individuals who are at the table helping to inform policy, helping to make policy such that their voices are heard...Those things matter.” *The views expressed in this report are the authors’ alone and are not necessarily shared by the “Hear My Voice…” organization or publications or the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. |

Author

Zila Renfro Major:Broadcast Journalism Year: Senior Multimedia journalist working to make a difference |