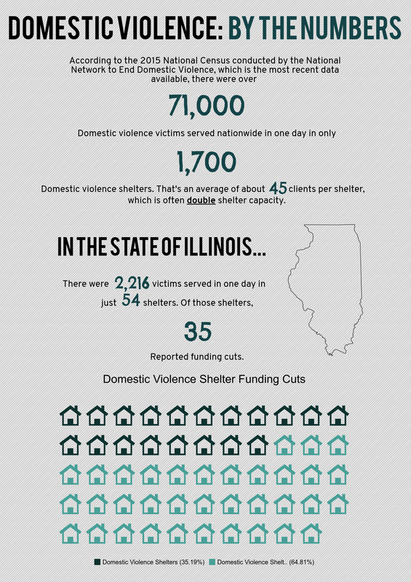

Abuse may be the only constant in the life of Faith Harper. Originally from Danville, Harper, now 51, has known abuse well since she was a young child. Her dad, an alcoholic, committed what Harper called “different aspects of abuse” against herself and her two siblings, which forced her to flee from home at 18 years old. “That was when I first stayed in a shelter,” Harper said, while taking a sip from a 7-11 Big Gulp. “I had to get away from there.” Unfortunately, Harper’s story is not uncommon. According to the 2015 national census conducted by the National Network to End Domestic Violence, which is the most recent data available, there were over 71,000 domestic violence victims served in one day in around 1,700 domestic violence shelters nationwide. In the state of Illinois, there were 2,216 victims served in one day in just 54 shelters, about 35 of which had reported government funding cuts. The Courage Connection Emergency Shelter, where Harper has been a resident since August, is the only domestic violence shelter in Champaign County. Marrella McMurray, the domestic violence services program manager for Courage Connection, said the organization had to be entirely restructured due to the lack of a state budget. “Thankfully our agency is big enough and has enough funding outside of state funding that we have been able to maintain our services,” McMurray said. “But there’s a fear that’s kind of there, lurking, of what’s going to happen to a lot of state funded agencies. It’s going to get a lot harder.” Harper is no stranger to shelters in the state of Illinois. She has stayed at shelters in Danville, Bloomington, and now Champaign. When answering questions, Harper spoke in short fragments with little inflection. She has ice blue eyes, and wispy gray hair, which was pulled back into a low ponytail at the nape of her neck with a scrunchie. One of her feet was in a medical boot- she recently had a bone spur scraped off of the knuckle of her big toe. She coughed often; she has a smoking habit she said she can’t seem to kick. She has piercings up the entirety of her ears, and a nose ring she has had for 22 years. She does not know how long her first shelter stay in Danville lasted- she said it has been too many years to remember. “My time was up,” she said, when asked why she left. “I went back home with my dad. I had nowhere else to go.” Shortly after returning home, Harper discovered she was pregnant. The baby died three days after she was born. “God needed an angel, and he took the best one,” Harper said. “Her name was Ashley.” Harper attended Danville Area Community College with the dream of becoming a therapist. After six months, she dropped out when she became pregnant with her son, Michael. “It’s been 30 years,” Harper said with a smile. “Me and his dad hooked up 30 years ago this Friday, to the day.” Harper said she still talks to Michael’s father, Sam, and that he visits her in the shelter- he lives right up the street. He was always involved in Michael’s life. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Harper’s other children. “My middle son is a rape baby,” she said. “I almost died.” His name is Marcus. Harper went on to have a daughter, Maya, the following year. Nowadays, Harper said her only child she really stays in touch with is Michael, who is 29 years old. He lives in Bloomington and is the third-ranking management position at a Wal-Mart. Maya, now 22, lives in Danville with two children of her own, and works at Circle K. Harper said when she last heard from Marcus, who would be 24 now, he was in Oregon. “Last time I heard he was in jail,” she said. “So I guess they’re all doing pretty good except for Marcus. Poor kid.” After giving birth to Maya, Harper and her children moved to Bloomington. She never married, though she said Michael always wanted her to end up with his father. To hear Harper tell it, the next 12 to 13 years of her life were relatively peaceful. In 2004, she even landed her dream job as a residential counselor at Chestnut Health Systems, a drug and alcohol rehab center. “I’ve had my own ups and downs with drugs and alcohol,” Harper said. She admitted she is still not sober. Unfortunately, Harper only had the job she loved for five years. In 2009, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer, and needed a hysterectomy. “Things got really bad after my hysterectomy,” she said. “I went into an emotional upheaval because of a lack of hormones- my health insurance wouldn’t cover the hormones I needed. I went bonkers.” When Harper said she went “bonkers,” she meant it. She quit her job. She moved all over the country- first to New York, then back to Illinois, then to Arkansas. She lived in a tent in the woods for a year. “When I came back from New York, I went to a shelter in Bloomington until I could get back on my feet, but I never did,” she said. “I lived in a tent in the woods after that, in the middle of an Illinois winter.” She then returned to the shelter in Bloomington. After a short stay, she went to live in Arkansas for a year, followed by two years in Florida. She returned to Danville about a year ago. “I was staying with Michael’s dad, down the road,” Harper said. “His kids all moved in, and the house is not very big. I ended up getting pushed out.” Harper’s official file at the Courage Connection emergency shelter said she was physically assaulted by one of her “step-children” in the house, which led her to flee. Every new emergency shelter resident must fill out a six-page long intake form when they first arrive. The questions range from gender identity (all genders are welcome, including males), marital status, and number of children. There is a detailed section about the nature of the offense inflicted on the person seeking shelter, broken down into three main categories: emotional domestic violence, physical domestic violence, or sexual domestic violence. Osajuli Cravens, the development assistant for Courage Connection, said the self-reporting is essentially the honors system. “We start by believing them,” Cravens said of the residents. “We are a client-first organization, so we always take our clients’ word for it.” There is a substantial amount of paperwork aside from just the initial intake form- there is a confidentiality agreement, a guide of rights and responsibilities, a parking policies acknowledgement, a conflicts and grievances form, a medical form, information about the Illinois Domestic Violence Act, and a form asking for specifics about the resident’s abuser. There, the resident can name his or her abuser, and give that person’s address, phone number, physical description, and vehicle description. This form also asks if the abuser knows where the resident is now, and if the abuser has any gang affiliations, or access to weapons. “We don’t disclose the location of the shelter publicly,” Cravens said. “People in Urbana know where it is, and if someone calls our number seeking help, we can direct them there.” The shelter has no sign aside from a large marker with its street address, so clients in need can find it. In order to get inside, one must buzz in and speak with a receptionist, who is monitoring the outside via camera. “We have two full time day staff who man the shelter,” said Marrella McMurray. “They work with residents and help connect them to resources, set goals for themselves, that kind of thing.” Courage Connection also offers legal assistance for victims seeking orders of protection, or residents who need help expunging their criminal records. There is even a P.O. box address residents can use if they are afraid or embarrassed to list the shelter as their home. McMurray said the emergency shelter has 10 rooms, and spots are given on a first-come first-serve basis. “We will put single women together in a room, but families will have their own rooms,” she said. “So if it was all families, we could accommodate 10 families. If it was all single people, we could accommodate a lot more, probably about 20.” The max number of people the shelter has accommodated at once was 15 women and 18 children, though currently, there are only 11 women and three children. McMurray said there is a wide range in the demographics of the shelter residents, but their age range is typically 20-45 years old. The shelter is billed as a 45-day program for residents to get stabilized and back on their feet, but there is not really a set number of days of how long someone can stay. “If someone is working really hard but just isn’t quite there yet; they’re waiting to get a background check approved for a lease or something like that, we’ll give them an extension,” McMurray said. “But once we hit that 60 to 70-day mark, we start to reach a max.” Harper is no longer a part of the emergency program, though she still lives in the emergency shelter. After 45 days, she moved to the transitional housing program offered through Courage Connection. “There is a rent component with transitional housing, because we emphasize self-sufficiency,” McMurray said. Admittedly, it is not a big component- it is 10 percent of the resident’s income. “We’re still offering them some support and assistance that they wouldn’t get if they were just living in their own apartment, but also looking at what it is like to be living on your own.” Tish Gatson is Courage Connection’s shelter coordinator for transitional housing. She helps the residents do paperwork, makes an individualized care plan for each of them, and helps connect them with outside resources. “We help them get food, clothing, and bus passes,” Gatson said. “We make that point of contact and advocate for them with other social services they might need.” Each resident is given 10 bus passes to start out with upon arrival at the shelter, with the opportunity to earn more through chores. “There is a job board of chores and every resident has one chore a week,” said Stephanie Corrales, a client advocate. As an advocate, Corrales works directly with the residents to help them set goals for themselves, and advocates on their behalf. “If they want to get more bus passes, they can volunteer to do more chores.” Harper was off from chores for a couple of weeks because of her surgery, but she just started working again this week. “It’s hard because it does still kinda hurt to walk, and it’s hard to get around,” she said. “But I guess that’s how it goes.” Residents have access to a food pantry on-site, free of charge. There is no “meal plan” or cook, but there is a kitchen where residents can make whatever they please. Each resident sets aside his or her own space in the refrigerator and on the shelves for food. “We get our food from donations and our monthly trip to the Eastern Illinois Food Bank,” McMurray said. Outside of the shelter, Harper also receives food stamps. She pays her transitional housing rent through what she calls “not a real job,” working as a receptionist at Champaign County Health Care Consumers once a week. She makes $265 a month. Her two goals when she first arrived at the shelter were to get an undisclosed felony conviction from 20 years ago expunged from her record, which Corrales said she accomplished, and to find herself an apartment. “We never have an issue with Faith,” Corrales said. “She’s like the person you’d go to if you had an issue. The other clients go to her and talk to her about their problems.” Additionally, Corrales said Harper attends every event Courage Connection offers. There are three weekly groups: a parenting group, a domestic violence empowerment and support group, and financial empowerment group, which focuses on budgeting, credit scores, and saving money. There are often guest speakers from the community who come and give lectures during the group meetings. “She participates a lot during the events,” Corrales said of Harper. “She’s really one of our best clients.” Lexi, another resident of the shelter who asked not to give her last name, said none of the other residents had any issues with Harper. “How could you not like Faith,” she said, smiling. “She’s such a sweet, calm woman.” For Harper’s part, she had no complaints about the shelter. She could not name one thing she did not like about it. “It’s almost like a family here,” she said. She said she gets out of the shelter a lot, mostly to doctor’s appointments and her job, but she said it had been hard for her to get around the past couple of weeks because of the recent surgery on her foot. When asked what her least favorite quality about herself was, she replied that it was her limited mobility. “My short term goal is to get through day-by-day,” she said. “My long term goal is still to get my own place, or at least a place with a roommate.” Corrales said Harper’s health problems were the main obstacle stopping her from getting a full-time job and being able to support herself. Harper said she hopes to move back in with Sam, Michael’s father, after his kids move out. She likes Champaign; she is centrally located between two of her children, Michael and Maya. “Both of them can come see me here,” she said. “I’m in the middle, they know where I’m at.” She said her typical days at the shelter are spent watching sports on T.V. Her favorite team is the Chicago Bears, and she is a big NASCAR fan. She especially loves Dale Earnhardt Jr. Though she said she does not have many contacts outside of the shelter, she does not feel lonely. “I know I’m loved,” she said. “I know I have a lot of people who care about me.” Harper said she cannot plan what the future will hold. Her life has been admittedly something of a whirlwind, with new heartbreaks at each turn. However, she is proud of how far she has come. “I’m a strong person,” she said. “To go through everything I’ve gone through and still be standing here, I think I’m doing pretty good.”

0 Comments

|

Maggie SullivanMaggie Sullivan is a senior majoring in news-editorial journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Experience: Freelancing-Chicago Tribune, real time news intern with Mashable in Los Angeles. Maggie was introduced to Hear My Voice by taking Dr. Collins’ multimedia journalism class, and she fell in love with the organization! Check out some of her other work here: https://www.clippings.me/margaretsullivan ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Articles

- Breaking Down Mental Illiness

- Aggregation

- Overcoming Domestic Abuse

- Children and Media

- The Continuous Fight for a Transformed University

- Not Everyone is Born Equal

- COPING WITH RACE-RELATED STRESS

- Stress Tips

- Diversity Qualifications

- When Girls Go For It...

- Untouched Topics of Domestic Violence

- The Human Library

- Selective Sympathy for Terrorism

- From Margin to Center

- Freedom of Speech = Safe Space? >

- Thank God It's Natural CEO Chris-Tia Donaldson

- Young Voices

- Features

- Podcasts

- Resources

- Custody Battle Ground: Kansas Kids

|

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals and their families. ACE, Active Centralized Empowerment and Inc. cannot be used without the written permission from Dr. Janice Marie Collins.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed